Why New Construction Cannot Solve the Climate Crisis

April 18, 2023 | By Chris Hague

While “cutting edge” approaches towards sustainability in architecture, such as net zero construction, are important sustainable design strategies, the current focus is misguided. New, net-zero construction cannot reduce global carbon emissions within the timeframe required to relieve the climate crisis. At current rates of new construction, it will take over 100 years to convert the building stock to carbon neutral (if 100% of new construction was net zero). However, the existing building stock does not share the same limitation. Why focus all our collective energy on the smallest lever arm of the solution (new construction), when we can achieve a measurable, global impact by focusing on existing building renovations?

Effectively, there are three methods to reduce carbon in the environment: Sustainable energy production, carbon emission reduction (excluding energy production), and carbon sequestration. Each method spans many sectors and cannot individually solve the carbon problem; a balance must be reached to create a measurable impact.

Architecture fits into two methods: reducing direct emissions and reducing energy consumption. The more green energy that can be produced, the less need there is for net-zero construction. Conversely, the more energy-efficient buildings there are, the less green energy infrastructure we need to build. Furthermore, the more green energy that can be produced, the more carbon sequestration can be performed. The more time we can give ourselves to solve the carbon emissions problem, the more market capitalization can be leveraged with more affordable techniques. More effective and aggressive techniques may be available, but if they are too expensive to be used, they will not be employed.

Ubiquity is key

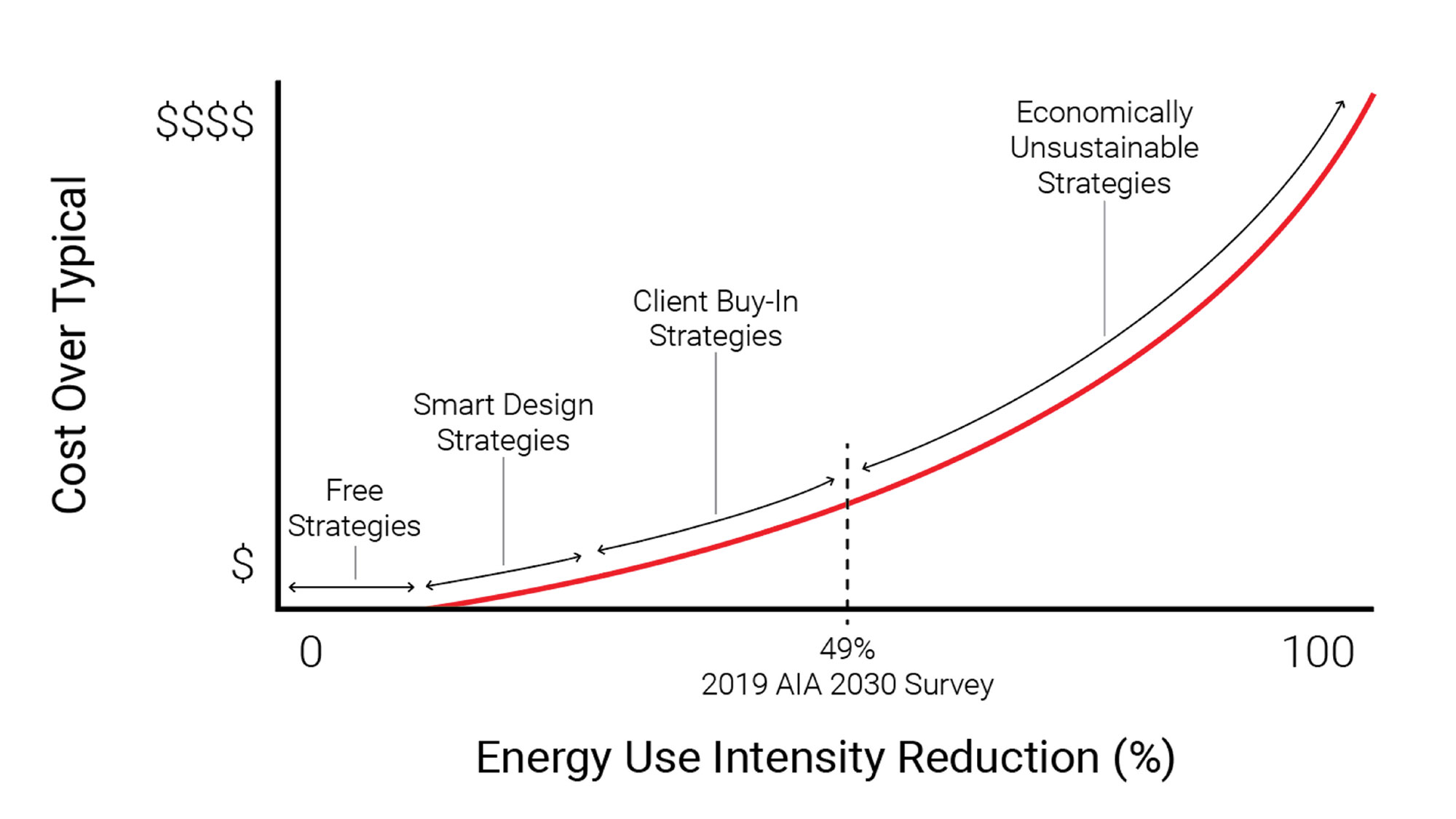

The prevailing industry perception is that if net zero construction is cost prohibitive, then clients are often unable to buy into it. In practice, there is limited reduction of energy use intensity through low-cost smart design strategies and user behavior augmentation. More effective and expensive methods for reducing energy usage require client sign-off and buy-in. If it is not economically sustainable, it cannot be ubiquitous. The cost vs. energy reduction curve works against net-zero projects but works in favor of widespread renovation of existing buildings that can collectively make a global impact with low-cost/low-yield reduction strategies. Ubiquity is key.

To create ubiquity, there needs to be affordable access. If the cost of entry to carbon reducing architectural renovation techniques decreases, market saturation will increase, and therefore the energy use of the average square foot of the global building stock will be reduced.

A first principles approach

Architecture is extremely complex, extremely expensive, and relatively long lasting, but there are precedents of major industrial paradigm shifts that were brought to fruition by building from the ground up, using a first principles approach. First principles are foundational assumptions that stand alone; they are the deepest axioms that cannot be deduced by any other assumptions. A first principles approach means starting from a core axiom and working toward a conclusion from there. In this approach, the conclusion can be consistently tested against the first principle from which it was derived.

For example, SpaceX and Tesla have decreased the cost of entry to space and sustainable personal transportation range by nearly a factor of 10 through first principles logic, resulting in an unprecedented market capitalization.

Just as first principles thinking has transformed the automotive and space industries, we need to provide a similar approach to address how the built environment can address the climate crisis.

The maximum annual impact of new construction is equal to the annual increase of new square footage built versus the existing global building stock. For example, if there is an annual turnover of 1% of the global square footage and 100% of those new buildings are net zero, global emissions only decrease by 1% each year. Looking at this from a first-principles perspective, new construction cannot achieve the necessary results in the amount of time required because it simply does not have enough market penetration, or ubiquity.

A call to action for the architecture industry

Global carbon reduction by new building stock will always be limited to the production of new buildings, but the existing building stock is only limited by its access to energy efficient renovation strategies and products. The architecture industry cannot solely rely on new net-zero construction to make a measurable impact in global square footage emissions; the math simply does not work out. Sustainable renovation techniques for the existing building stock and energy efficient products must have a lower cost-of-entry to gain market capitalization if we are to meet sustainability goals in time.

By leveraging existing building stock, the market has an opportunity to make achievable impact at a global scale. If the architecture industry can make a greater effort in renovating the existing building stock through cost-effective techniques and products, we can help achieve the global carbon reduction goal at the triple-point of reducing carbon production, sustainable energy production, and carbon sequestration.

The idea is much simpler than its execution, but the benefit can be immense, far reaching, timely, and far more effective than solely relying upon a net-zero building stock, so I believe it is a task worth undertaking.

For media inquiries, email .