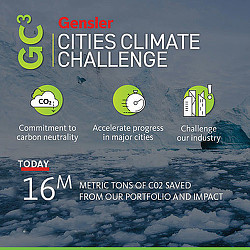

Coastal cities face a harsh reality: The effects of climate change are increasingly evident — and urgent. In 2018, we witnessed one of the warmest years recorded. The Earth’s oceans also experienced the warmest year on record. According to the journal Science, ocean warming is accelerating 40 percent faster on average than previous United Nations panel estimates five years ago. As the ocean continues to warm, sea levels will rise, storm surges will become more frequent, and rainfall more intense. In fact, sea levels could rise between 3 and 6 feet by 2100, according to a study in the journal Nature.

It’s abundantly clear that cities must plan aggressively for climate change, and this is especially true for coastal cities. From Miami to Manila, cities situated near coasts are particularly vulnerable to climate-related disaster events, from hurricanes, to excessive heat, sea level rise, and flooding.

For cities to protect the people who live and work in them and to continue to thrive in the 21st century, local and regional governments, in partnership with the private realm, are going to have to adopt innovative resilience strategies toward designing with water in mind.

— International Energy Association

The good news is that many cities are already implementing progressive strategies for a range of issues to endure the strains precipitated by climate change. Not surprisingly, coastal cities are rethinking their relationship to water. In addition to natural defense strategies like coastal dunes and wetlands to inhibit flooding, city planners are putting streets, parks, and other open spaces to work.

Take Houston. After Tropical Storm Allison devastated the city in 2001, city leaders adopted more green infrastructure to harvest and store water from flash floods for reuse elsewhere. The city identified and rebuilt high-flood-risk streets, converted soccer fields to temporary ponds to absorb surging water, and repaved parking lots with permeable materials that can channel water to sub-surface water tanks. Strategies like these can help lessen the influxes of water, minimize damage, and allow the city to recover more quickly. When Hurricane Harvey hit 16 years later, the city was better prepared.

In Miami, a Gensler research team led by Ana Benatuil is exploring how zoning codes and development policies could require communities at higher elevations to acquire increased levels of density to insulate them from flooding. Low-lying areas would be zoned as parks and wetlands, acting as buffer zones. A man-made delta integrating water into the urban fabric would transform streets into canals, while an elevated transportation network would serve the needs of a denser city.

PLANNING FOR EVERYDAY RESILIENCE

Beyond resilience to acute shocks, everyday resilience is also key. In China, where urban sprawl and impermeable materials have worsened flooding, government officials have embarked on an ambitious goal: for 80 percent of urban areas to absorb and reuse at least 70 percent of rainwater by 2020. The country’s “sponge city initiative” aims to replace concrete pavement with green roofs, wetlands, rain gardens, and other green infrastructure and permeable surfaces. The program rethinks stormwater as a resource to augment the cities’ water supplies, while alleviating long-term threats from sea level rise.

Technology is also playing a crucial role in helping cities create strategies to deal with sea level rise. Just as urban planners will leverage canals and other solutions to manage higher water levels, building designers and operators will need to consider materials and systems capable of withstanding extreme weather and water damage. As automated building management systems become more responsive, for example, predictive technologies and real-time environmental data can alert operators ahead of time and help mitigate urban impacts. At the building level, low-tech solutions like raising ground floors, using durable materials, rainwater and gray water harvesting, and constructing water-tight façades and interiors are having outsized impacts. Our Impact by Design research outlines some of the strategies that the built environment can leverage to make an impact through design.

Johnson Controls Headquarters Asia Pacific in Shanghai, for example, employs a full range of smart building solutions. Through smart systems, such as a siphonic drainage system that transports rainwater collected on the roof and gray water collected from showers and sinks to a storage tank in the basement, the building is expected to reduce water usage by 42 percent via its gray water recycling and stormwater recapture facilities.

BEYOND SUSTAINABILITY: BOOSTING LIVABILITY

But more than just technological solutions, cities must also address the unintended socio-economic costs precipitated by storm surges and flooding, such as loss of property, transportation and business disruption, and adverse health effects. Beyond sustainability, the designs we choose must be life-enhancing while reinforcing the connections that define the human experience. This is why resilient design must also include public and private partnerships that can improve everyday living standards.

Regions like Greater Miami, which has been called “ground zero” for sea level rise, have joined The Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) network, which helps cities around the world build resilience to the social, economic, and physical challenges of the 21st century. As 100RC members, Miami-Dade County, the city of Miami Beach, and the city of Miami will have access to $200 million in tools and services in the private, public, academic, and nonprofit sectors. Such partnerships help cities cope with shared, complex local challenges around sea level rise, aging infrastructure, and more.

RESILIENCE IS A LONG-TERM INVESTMENT

Planning for resilience is an investment in a city’s longevity. We have a responsibility to not just respond to massive climate events, but to anticipate and prepare for them. This will require continued collaboration between cities, the design industry, and the public and private sectors to keep up with rapidly evolving climate patterns and human needs.

If we think about water as an asset, rather than a threat, we can design cities to plan ahead and leverage storm and flood water, rather than resist it.