Planning Resilient Communities

The word RESILIENCE sparks thoughts of natural disasters. Three current Gensler projects show that it’s really about reviving and sustaining the qualities that make a place uniquely a place.

While disasters grab headlines and set defensive agendas for resilience planning, they’re only part of the story. Resilience is also about strengthening communities economically and socially, as three Gensler projects illustrate.

Baltimore’s resilience challenge is to jump-start local prosperity without harming community cohesion and pride. China’s Yunnan Province wants to balance economic and population growth with the need to preserve ample green space for agriculture, wildlife, and recreation. Makkah is the focus of national efforts by Saudi Arabia to diversify its economy, provide jobs, and maintain a high standard of living.

While environmental issues run through all three, their planners’ real focus is on resilience as future-proofing—ensuring that each community can thrive, but thrive on its own terms, specific to the place. Local engagement includes working with tradition to avoid or resolve conflicts. Nature is part of the existing context, along with other dimensions that make a community what it is. Gensler works with all of these issues to foster, channel, and sustain growth effectively.

Makkah Techno Valley spurs innovation in the context of Saudi Arabia’s climate and traditions.

Resilience as local revitalization

“Planning at a community scale too often discounts the community itself,” says Peter Stubb. He and Elaine Asal were part of a Gensler team that worked with seven Southwest Baltimore neighborhoods to plan their revival. The effort stands apart from traditional planning projects in that it allowed residents in this disinvested and troubled corner of the city to serve as true cocreators. “It was about creating a resilient process, a malleable framework in which residents could find their own voice,” Asal says.

The project was also unique in that the energy needed to drive it was already in place when Gensler arrived at the table. “The neighborhoods formed working groups,” Asal explains. Each group explored such issues as commercial development, housing, and neighborhood preservation and branding. “It was exciting for us to translate their work into more formal ideas.”

The team met with working groups’ leaders to distill key issues, bolstering the groups’ findings with quantitative and qualitative data and urban design analysis. It kept different stakeholders in the loop and convened a series of public design workshops. The resulting Southwest Partnership Master Plan outlines a set of design recommendations that build on a framework of “big ideas.”

This socially focused approach to planning enabled all involved to understand the existing urban context better. It also spawned engagement strategies that helped the neighborhoods arrive at low-cost, targeted ways to revitalize. These efforts were key to ensuring that the different neighborhoods’ visions of their future aligned. “By involving every neighborhood, we got them involved with each other. They came into the process with separate agendas, but then saw the need to connect,” Asal says.

One of those engagement strategies was an “analog hackathon” in which members of the community brainstormed what locally based projects and activities could be carried out quickly at a grassroots level. “The ideas put forward included adopting buildings that people would clean up on weekends; creating events around a circus perfor-mance; and tracing the history of a neighborhood and sharing it online and at local events,” Stubb notes.

The seven neighborhoods are now forming a 501(c)(3) entity to carry out the master plan’s recommendations. Their willingness to invest time and energy in Southwest Baltimore despite its challenges speaks to and is predictive of its resilience.

Resilience as regional well-being

While the Baltimore planners focused on that city’s revitalization, their colleagues in China faced the challenge of managing urban growth without creating sprawl. Shanghai-based Tom Ford says that Qujing, located in a fertile valley in Yunnan Province—the headwaters of the Pearl River—reminded him of California’s Napa Valley a generation ago. “Despite regional growth, Napa succeeded in preserving what makes it what it is: its vineyards and its beauty.”

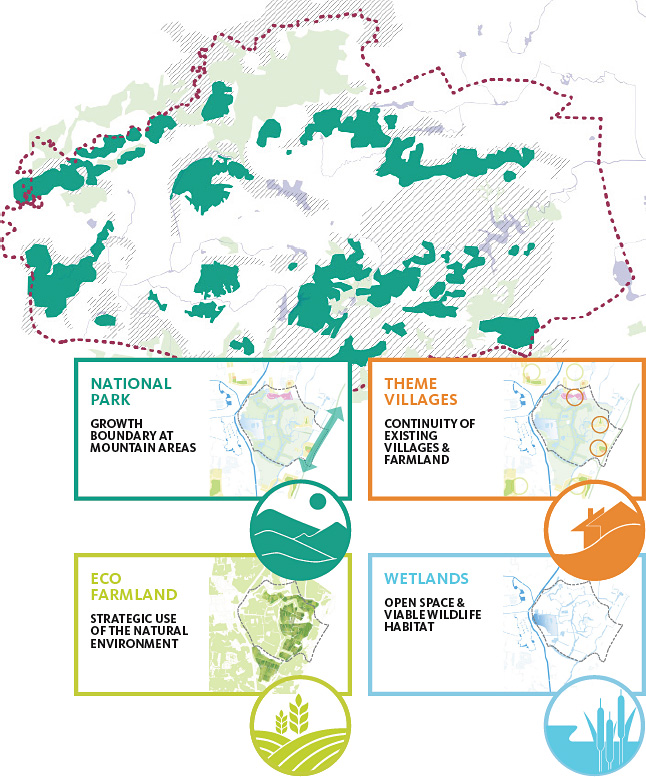

Qujing anchors a comparable area. Believing that resilience is achieved by reinforcing existing ties to land, culture, and family, Ford and his team aimed to bolster people’s health and wellness, as well as protect farming, recreation, and natural features. “The goal is to absorb new growth in a synergistic way, keeping families together and the green space intact,” Ford explains. To accomplish this, the Gensler team planned circulation, and defined development boundaries around the area’s strong but not always visible social anchors.

“The air is great in Qujing,” Ford says. “It’s also a place where the older generation lives with their families. Those ties matter and any redevelopment has to consider them. So wellness rose quickly to the surface. But spas and recupera-tive centers have broader appeal in China, with its aging population.”

The everyday activities of an agrarian economy produce specific community settings, says Gensler’s See Chen Chang—“small places where people dry chili, spices, and corn, for example. Through our fieldwork, we realized that people value and maintain these spaces. They gather there during commmunal festivals and also as part of daily life, so we’re making them part of any new development.”

“China’s tendency is to see open land as ripe for development,” Ford says. “Napa Valley was once looked at similarly, but the community pushed back. Qujing’s valley is now at the same cross- roads.” The team incorporated urban growth boundaries in the plan to help persuade local officials to see that the valley’s economy depends on it, he explains. “The amenity is already there,” says Ford. “The challenge is to keep new growth from encroaching on it. Containing new growth preserves the valley and strengthens its communities.”

Sustainable living at human scale

Carlos Cubillos and his team faced a blank slate as they developed a plan for an entirely new community, Makkah Techno Valley, focused on developing the tech sector in Saudi Arabia. To attract the talent such a venture needs, the planners pressed the idea of supporting sustainable living at human scale. Urbanity in this context meant blending work and the rest of life, and making daily life more livable. To counter the intense summer heat and ensure year-round walkability, the planners wove in shading and breeze corridors, and created outdoor settings that provide storm drainage to mitigate sporadic floods. Walkability matters, Cubillos explains, because “innovation can take place anywhere. It doesn’t necessarily happen in a lab.”

Several universities are active partners, with classrooms for knowledge transfer collocated with nascent businesses. Making the outdoor spaces in between them a feature of the new community resonated with students, Cubillos adds. “It supports how they live and work, and speaks to their technological ambitions, but its roots are in the place and culture, which guide how people interact.” It will be a “town without gates” that invites people to collaborate—as they must to generate new ideas—without overstepping bounds.

This meant making community life more intuitive, Cubillos notes. “The innovators have families, too, so tradition is in play. So we proposed to let community happen in a more open way.” Separation is provided where it matters, but this is not a walled town. “It’s designed to support the flow of people’s everyday lives in harmony with their society’s requirements,” he says.

Resilience is as diverse as place itself

Places are markers for the intangibles that people really cherish: memory, culture, and family, along with hopes for the future. When planners talk about resilience, they’re definitely thinking about natural events that are part of the unfolding history of a place—although potentially more problematic as populations grow and people start living in environmental danger zones.

But there’s more. “Resilience is also about making the connections that matter to a community durable under changing conditions,” Stubb explains. He and other Gensler planners tasked with promoting resilience find that a lot of reinforcement for place comes from steps to make that place more social. When people ask, “How can we keep things as they are?” they’re expressing apprehension about the unknowable future. The better questions to ask are, “What do you love about this place? What works well and what doesn’t?”

Resilience accepts a world that’s constantly in flux. How do you discover new truths and strengthen old ties and roots? It takes early and ongoing conversation, intensive efforts to build consensus, and a constant grounding of the new in each place’s nature and self-knowledge. These are planners’ tools of resilience—how they surface and burnish the behaviors and traditions that lead communities to invest their hopes in a place, whatever its challenges.

Alec Appelbaum teaches at Pratt Institute, writes for Fortune, the New York Times, and other publications. He also teaches a climate-readiness curriculum for K–12 students, AllBeforeUs.