In cities around the world, people are feeling the strain of housing. From London to San Francisco, rapid urbanization is causing a serious housing shortage and escalating prices, largely because we simply have not built enough in recent decades to keep up with the growing demand.

In addition to the burden on renters and buyers, the housing shortage also impacts entire economies. A McKinsey Global Institute report estimates that the issue costs the California economy alone between $143 and $233 billion per year in the form of reduced consumption — due to fewer dollars in consumers’ pockets — and lowered construction output.

The housing crisis cuts at the very heart of what makes cities successful and vital. To change this course, we need to develop innovative and inclusive housing solutions. Here’s a look at some of the possibilities Gensler is exploring.

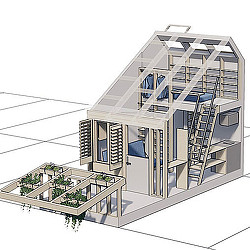

This is the model we’re testing in Los Angeles with the Ambrosia project, which is intended to address the city’s homelessness crisis. Consisting of prefabricated modular units that will house between 100 to 120 formerly homeless residents, Ambrosia will function as a prototype for a permanent supportive housing (PSH) solution. In an ongoing partnership with Skid Row Housing Trust, we designed this PSH approach to resemble a retail rollout, wherein the prototype can be quickly constructed, assembled, and applied across various locations as needed.

INVESTIGATING MIXED-INCOME SOLUTIONS

By incorporating both market-rate and below market-rate housing units, mixed-income developments help cities tackle the affordability crisis without isolating those of lesser means.

At Woodlawn Station, a mixed-income development located in Chicago’s South Side, Gensler helped to take the approach a step further. Working with the Brazier Foundation, the Preservation of Affordable Housing, and Greenlining Realty USA, Gensler created the master plan for the Woodlawn neighborhood and designed the 70-unit Woodlawn Station housing development. The master plan is aimed at helping spur reinvestment in the South Side, while the housing development itself uses ground-floor retail, modern finishes, and transit proximity to attract residents of various incomes.

SPOTLIGHTING THE NEW CO-LIVING LIFESTYLE

Students are another demographic affected by the lack of affordable housing. Yet they’re not willing to compromise on accommodations; today’s undergrads are looking for a co-living solution that’s more than the traditional dorm room.

900 Hilgard, adjacent to the UCLA campus, offers precisely the kinds of options desired by the college set. It creates a 16-story vertical living and learning community by reallocating space from the typical dormitory-style units into shared spaces for studying, cooking, socializing, and recharging. While this project targets students, the integrated co-living model it embraces is gaining traction as a broader solution across cities — especially with recent graduates who face intense competition for entry-level housing.

EXPLORING EMERGING HOUSING MODELS FOR SENIORS

Senior housing is another area drawing on the benefits of co-living. And it’s essential that it does so. The world is shifting toward a demographically older population: in the last century, the number of Americans ages 65 or older increased tenfold. Our research shows that people are living longer and healthier, and they’re passing on the traditional retirement home. Projects like Fountainview at Gonda Westside in Playa Vista, California, are designed to support residents’ desire to remain active and engaged with the life around them by combining private living with assisted care and amenities that are centered on social connection.

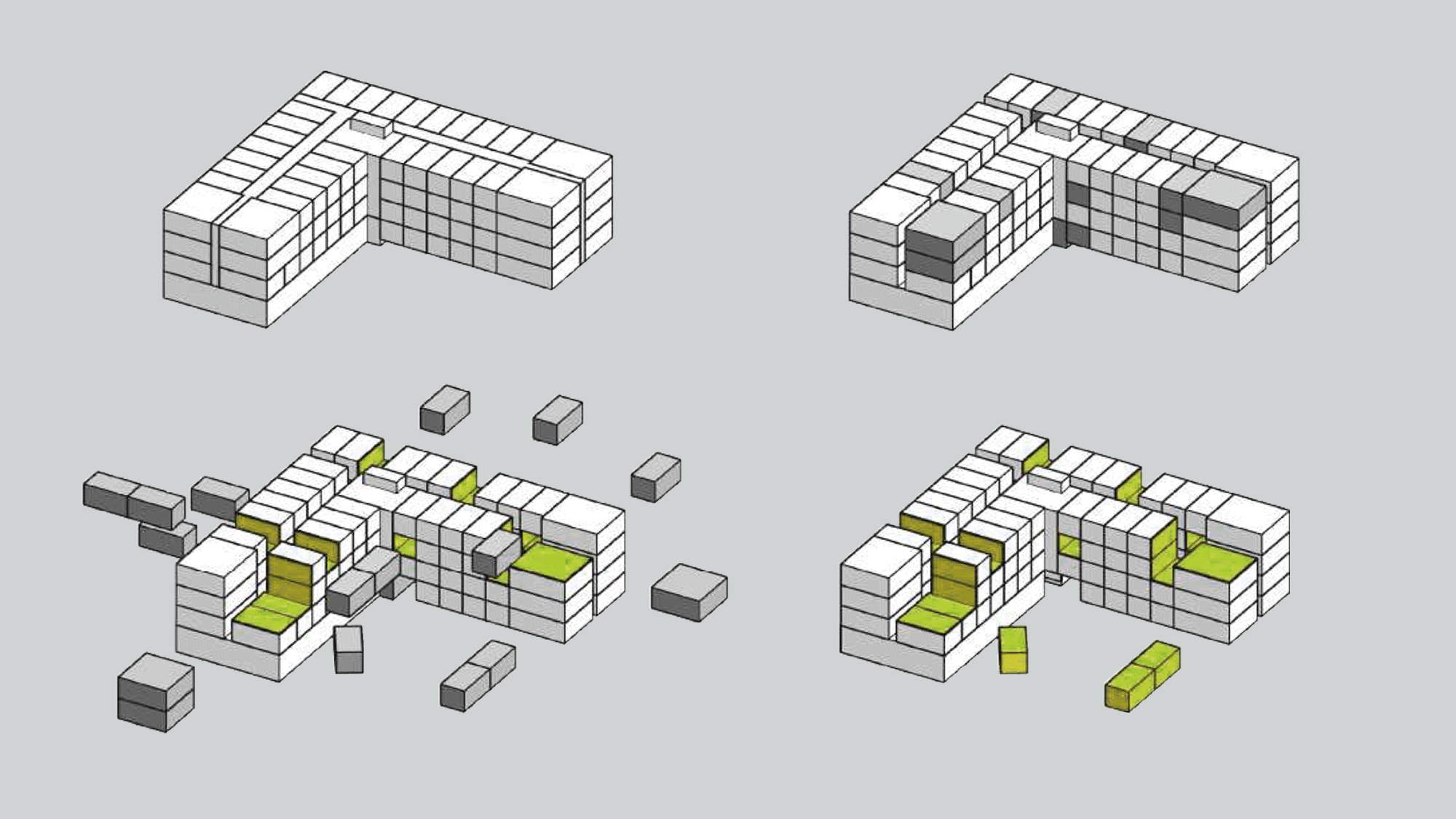

DESIGNING FOR FUNCTIONAL CONVERTIBILITY

The surest way to maximize urban residential space is to eliminate parking. A longstanding requirement in many cities, parking creates a burden for new buildings, significantly increasing construction costs while eating into livable space. That cost burden is ultimately passed on to building occupants, resulting in $1,700 in additional annual rent for the average tenant. But some cities, such as Buffalo, Hartford, Minneapolis, and San Francisco, have removed their parking requirements.

Along with these changes to parking, there are also shifts in urban mobility that architects are actively considering. For the 8th, Grand, and Hope project, in downtown LA, Gensler is designing a garage that can be phased into residential use over time.

The parking issue illustrates how housing policy is bound up in myriad other urban livability factors — such as transit planning, climate change, and economic inequality, to name a few. Yet at the center of that tangle of elements is the question of what value we place on the well-being of urban residents. If we truly believe cities to be dynamic places of opportunity for all, then we must create housing options that enable more people to feel welcome, secure, healthy, and happy. A greater range of housing options aimed at a larger swath of people is the only way to ensure that our cities live up to their full potential.